by Claudia Viggiani

translated by Steve Barley

In order to understand a work of art it is almost always necessary to know its historical context and how it came about in the hands of the artist who conceived it and gave it life.

But when we think of an artist it often isn’t possible to place him in the period in which he lived and the social context in which he developed, above all as a human being.

If then we discover a biography of the artist, one that is well-written with clear historical and geographical references and without romanticized frills, we realize how necessary an “in-depth” understanding is for our individual cultural awareness and for the pleasure and satisfaction which depend on it.

The word culture has a deep and absolute significance since it derives from an action: that of “cultivating” (colĕre in Latin) study and experience in order that we may thereby attain knowledge.

Having a wide and enhanced perception of something, retaining a notion in the mind, having an exact and precise knowledge of a work of art, possessing and knowing how to distinguish the experiences which are necessary in order to understand someone or something, in brief – acting in such a way as to allow us to discover, experiment, study and understand – is at the root of culture.

We cultivate our studies to gather the fruits of knowledge.

But cultural awareness can also be inherited, absorbed, by means of words and images acquired as we progress through the entire arc of our lives.

The most fortunate among us are exposed to a passive colĕre thanks to the cultural heritage of our country and the cultural awareness which our families bestow on us.

I am referring to oral testimony and to intellectual and monumental works: to ancient, ancestral knowledge, comprehended, narrated, written, built and passed on through the centuries to us in the present.

Our civilization is especially fortunate in this respect because it has benefitted from an exceptional wealth of cultural assets, material and immaterial, for which we are all at the same time both guardians and messengers.

Before we look at a painting, a sculpture, a piece of architecture or any work of art, we should remind ourselves that we must become familiar with the man or the woman who made it and try to understand the context from which it stems.

Only in this way can we sow within ourselves the seed of that information which will transform itself in erudition, in awareness and, only lastly, in culture.

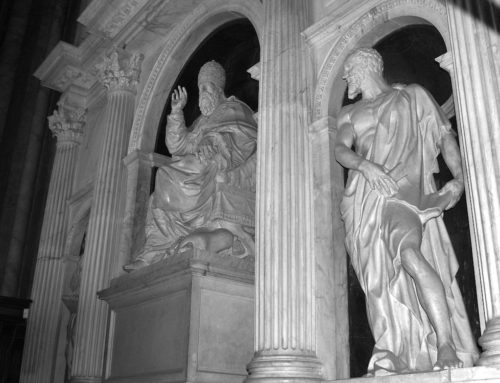

Michelangelo Buonarroti, Ancestors of Christ: Nahshon and his Mother, c. 1511-12, fresco, Sistine Chapel, Vatican Museums

Talking about culture is unimportant; culture is action. Action which, through a series of well-defined processes, often brings us to an understanding not only of a work of art, but of the whole of humanity in its infinite expression.

In the first lunette, high up on the left wall as you enter the Sistine Chapel through the small door under The Last Judgment, you see, on the right, Nahshon (Naasson), son of Amminadab, chief of the tribe of Judah in the desert and commander of an army of 74,600 men. Nahshon’s son, Salmon married Rahab and his grandson Boaz married Ruth (1Chron. 2:11-15; Ruth 4:20; Matt. 1:4-6, 16; Luke 3:32).

The young man is depicted reclining with one leg outstretched and resting on a wooden bench, his brow is furrowed and his arms folded, lazily hidden under his cloak. His surly attitude makes reference to the sloth and insolence which brought him to a refusal to read The Book of the Law which lies open before him.

On the left of the lunette is his mother, or perhaps his wife, looking at her reflection in a mirror, absorbed in a vanity which precludes her seeing anything else.

In the woman’s hand mirror we see a figure which differs from apparent reality: the face is faded and gloomy and nothing of the woman’s beauty, including her blond hair tied up in a ponytail and her wealth, denoted by her gold earrings, is evident in the reflected image.

Michelangelo wanted to depict these two ancestors of Christ, who did not want to recognize the laws dictated by God to Moses on Mount Sinai, blinded as they were by ignorance, self-satisfaction and presumption.